“Trust takes years to build, seconds to break, and a lifetime to recover” so the saying goes. This was my first thought when learning about Brazil’s second downgrade. The message that Brazil broke the market’s trust is now being transmitted around the world. The Financial Times says Brazil switched places with Argentina – a grinning Macri is proclaimed as the new hope for Latin America. Meanwhile, The Economist’s cover shows a disappointed Rousseff, the downgrade highlighted as the tipping point for the resignation of the market’s beloved Finance Minister, Joaquim Levy.

After years outside the investment-grade club, in 2008 Brazil first received the “international seal of approval” from Standard & Poors. By September 2015, the same agency was the first to change its mind. Then, on 18 December the downgrade by Fitch confirmed Brazil was back to junk (at least for investment purposes). But what does the downgrade really mean for the B of last season’s most trendy acronym [BRICS]?

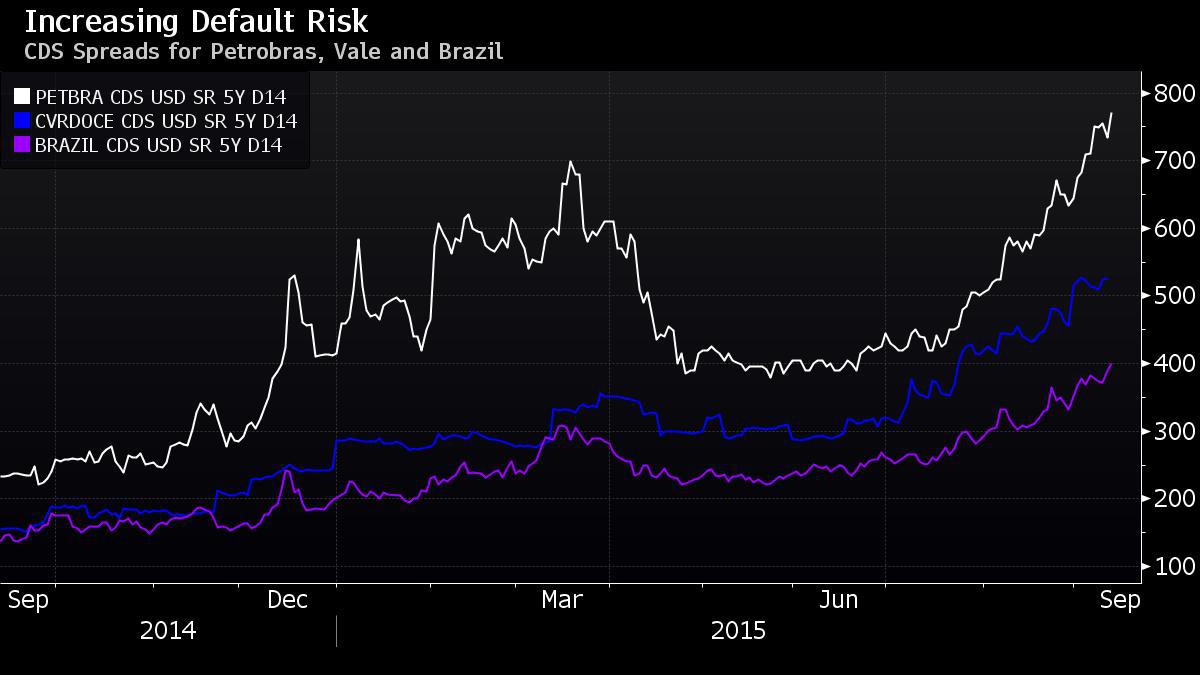

At first glance, it may seem nothing changed, or will change. The dollar rose “just” 1.47% following the news, and capital outflows didn’t suggest a crisis. One might even think that “No one will listen to the same rating agencies that got it so wrong in the 2008 crisis”. But, it’s not that simple. Back in 2008 ex-President Lula equated gaining investment grade to a watershed moment for Brazil: Brazil would be taken seriously, attracting more investors, increasing business and consumer confidence, and having access to cheaper credit. The opposite has to be true – not only for Brazil, but for all countries that experience a downgrade.The first and most obvious impact of leaving the investment grade club is reduced access to credit, trading a U$15 trillion pool of finance, for one worth U$2 trillion. Joining the ranks of the “risky” also means more expensive credit for everyone – from government to companies, banks to citizens. Investments are postponed, jobs are cut and delinquency rates increase; at the same time, consumption and production fall, dragging GDP growth.

Another likely effect is currency depreciation. With no seal of approval, investors may conclude the risks of investing in a “junk” country offset the potential gains and opt to leave, taking their dollars with them. Some, such as Pension funds, will be obliged by regulation to disinvest. In Brazil, JP Morgan estimates £3.8bn of “forced selling”, while the market expects the Real to depreciate by a further 13% in 2016 (following 40% depreciation in 2015).

A weaker currency means a lot. First, it means higher inflation. In 2015, the direct impact of currency depreciation in Brazil was 56% inflation on cooking gas and 35% on oil – affecting everything from transport fees to restaurant prices. Higher inflation means decreased purchasing power and falling consumption. It also means higher domestic interest rates, further depressing activity and protracting the recession, while worsening debt stability (through increased debt servicing costs) and prolonging the period of “junk status”. Finally, a weaker currency also means higher costs of dollar denominated debt for companies – such as the Brazilian oil giant Petrobras which has almost 75% of its debt in dollars – further constraining investment, production and growth.

Depreciated currencies can bring positive externalities too, especially by boosting exports and improving the trade balance. They can also attract bold foreign investors looking for good quality assets “for sale”. Nevertheless, we should remember that popular sayings are popular for a reason. Downgrade, like trust, is a big deal, and Brazil will wait years to recover it.

Texto publicado originalmente no blog Economics Matter do Foreign and Commonwealth Office do governo do Reino Unido, e também veiculado pelo blog Econ +.