Convidados Especiais | Miguel Bandeira

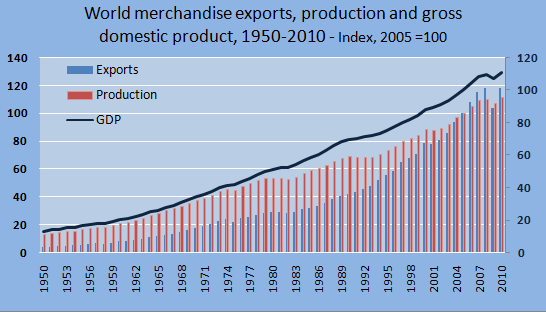

Over the last century international trade expanded at an incredible pace. According to figures from World Trade Organization (WTO)[1], in 2010 the volume of world merchandise exports was about 30 times higher than it was in 1950, which means that within this period it increased at an annual average rate of almost 6%. However, despite this enormous increase, advantages and disadvantages of international trade are still a matter of several controversies.

[caption id="attachment_1345" align="aligncenter" width="546"] Data Source: World Trade Organization (WTO)[/caption]

Data Source: World Trade Organization (WTO)[/caption]Economists often argue in favour of free-trade based essentially on the concept of comparative advantages created by the british economist David Ricardo in the XIX century. The main idea is that with trade each country will produce relatively more of the goods for which they have a comparative advantage and this will make both countries better-off than if they lived in autarky. In other words, trade allows countries to choose a bundle of consumption that is outside their production possibilities frontier and so it increases ‘national welfare’.

From an empirical perspective, the majority of the results in the literature corroborate the idea that trade improves the standards of living of a country[2]. For example, Feyrer (2009) estimated that an increase of 1% in trade tends to lead to an increase between 0,5% and 0.75% in the real GDP per capita and, moreover, trade can explain about 17% of the variation in growth rates across countries between 1960 and 1995.

But so, if trade causes such economic benefits, why barriers to free trade still exist? And furthermore, why some groups are against free trade?

The answer to these questions is that trade does not necessarily make every single individual better-off. Suppose, for instance, that a country has a comparative advantage in goods that are intensive in high skilled labor. After opening to trade this economy will produce more of goods that are intensive in high skilled labor, so the wages of high skilled labor will rise whereas wages of low skilled will decrease.

This illustrates a point that usually is not clear in economists’ arguments: the equilibrium under free trade is not Pareto superior to the one under autarky since, as the example above illustrates, ones are better-off and others worse-off. What economists are trying to say when they state that free trade increases ‘national welfare’ is that there is a potential Pareto improvement in opening to trade[3], which means that gains from trade are large enough so that if there is a way to redistribute them is possible to make every individual better-off.

The question is that redistribution is difficult and quite often unfeasible and this explains the claims of some groups against free trade. But still, if trade has positive impacts on the aggregate, why governments cede to the pressures of the minorities negatively affected?

Usually this happens because the groups that would lose from international trade are usually more concentrated, informed and organized than the potential winners from free trade.

This is precisely what happens in the US sugar market, for instance. According to Krugman and Obstfeld (2010), prices of sugar are 60% higher in US market than on world markets due to the policy of restrictions on imports of this good. Estimates indicate that this policy cost about $1.5 billion every year to American consumers or, equivalently, $ 6/year per US citizen.

Perhaps, $6/year is too little to make consumers claim about it, and actually many of them not even know that they incurring in losses. But, for sugar producers definitely “extra” thousand dollars in revenues justify their strong organization to pressure for the maintenance of restrictions to imports, even though these policies are negative from an aggregate perspective.

Miguel Bandeira Economista formado na FGV-SP, mestre na Nova School of Business & Economics, Lisboa/Portugal ![]()

References:

Autor, David. 14.03 Microeconomic Theory and Public Policy, Fall 2010. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare), http://ocw.mit.edu (Accessed 10 Oct, 2012). License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA

Frankel, Jeffrey and Romer, David (1999). “Does Trade Cause Growth?”. American Economic Review 89(3), 379-399.

Feyrer, James (2009). “Trade and Income – Exploiting Time Series in Geography”. NBER Working Paper #14910.

Krugman and Obstfled (2010). Economia Internacional: Teoria e Política. São Paulo, Pearson Prentice Hall, 8 º edição.

Noguer, M. and Siscart, M. (2005). “Trade raises income: a precise and robust result”. Journal of International Economics 65, 447-460.

Pyndick, R. and Rubinfeld, D. (1995). Microeconomics. Prentice Hall, 3rd edition

Foot Notes

[1] Link: http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/its2011_e/its11_appendix_e.htm

[2] See Frankel and Romer (1999), Noguer and Siscart (2005), Feyrer (2009) and references therein

[3] See Autor (2004)